On the way to our Christmas party this year, my colleague and I darted onto a tube train as the doors were closing. Deep in conversation it took us a few stops to realise we were going the wrong way. It’s a disconcerting experience to realise you are not going in the direction you were expecting. But at least in this case the mistake was our own, was easily reversed and we still arrived on time. Much more frustrating are the occasions when a clearly advertised experience is different to expectations.

In art, music and sport we become accustomed to our favourite performers and their own styles. Occasionally they choose to move in a new direction with mixed results. Beyoncé’s foray into country music in 2024 was met with almost universal approval, but more often than not stylistic shifts are less successful. The England cricket team’s recent heavy defeats to Australia while playing their far more aggressive style of “Bazball” is a case in point. It was this disastrous series that got me thinking about style drift in fund management, or specifically, why it happens, the risks it creates and why it matters most, not for managers, but for asset allocators.

The importance of style

In investment, as in music or sport, a manager’s style reflects both deeply held beliefs about what works best and an approach honed over many years. It is not simply the chosen route by which you seek to make returns, but the foundation for managing risk and making decisions consistently.

For asset allocators, styles are central to portfolio construction. Allocators combine different assets and investment styles to achieve diversification across market environments. A clearly defined style allows them to understand not only what sort of returns a manager is targeting, but also how those returns are expected to be generated and in what circumstances they expect the asset to perform best (and worst). Crucially, it is only by staying true to your style that you can guarantee to clients that the fund does what it says on the tin. Achieving this requires two things: a clear and unambiguous definition and the credibility that you will stick to it even when it becomes uncomfortable.

Some managers may be reluctant to define their philosophy too narrowly, arguing that explicit constraints will inevitably stand in the way of performance. They may even be proven right in the short term, but the cost of this flexibility is borne by the client. Without clear definitions, they forgo the control that comes from knowing exactly what they own, replacing it with hopes and crossed fingers. This trade-off becomes increasingly problematic in complex asset allocations, where each fund is expected to play a specific role within a broader objective. When the fund is no longer playing the part it was cast, the integrity of the overall portfolio is weakened, often without the allocator realising it at the time.

Under pressure

If style is so important, then where does the motivation to style drift come from? The answer is of course performance, or more precisely, the pressure to perform. Nowhere is this more visible than in elite sport. In 2022, England’s cricketers had endured a torrid run, winning only one out of their previous seventeen test matches. As a result, they faced mounting calls from the media, fans and management to “do something”. The shift to a more aggressive playing style, which became known as ‘Bazball’, was their answer: a radical departure from convention, designed to deliver victories while entertaining fans and players alike.

After two years of underperformance, one can understand why quality managers are feeling a similar pressure to stray from their typical hunting ground. Even investors with a long track record and a well-articulated philosophy are not immune, particularly as styles can remain out of favour for some time.

This dynamic is often driven less by the investment team’s beliefs and more by business realities. On an employee level, if remuneration is structured around short-term performance, then individuals will try to chase higher returns due to their own financial constraints. On a firm level, if a company has not prepared for these inevitable events, it may not be able to get through a period of weak performance and outflows, increasing the burden on the fund management team to “do something”. The pressure may even come directly from clients, who may themselves be facing similar commercial realities.

It is in times like these that managers who have given themselves plenty of wriggle room will feel most grateful for it. Without clearly defining their style, a manager can capitulate, while claiming to stay true to their loosely defined philosophy. The overlap between styles and the ambiguity of labels like “quality” or “value” make such transgressions all the easier.

Investment history is littered with examples of fund managers who changed their style because a dominant theme was causing them to lag behind peers. During the low interest rate environment of 2019-2021, many value managers shifted into higher quality names, lured into the higher multiples with rates looking like they would never get back above 1 per cent. Similarly, the 2006-2008 period saw certain growth managers drift into cyclicals, arguing that demand in China had become secular rather than cyclical.

We can also read about the managers who remained disciplined, only to find themselves out of a job anyway. Tony Dye was the CIO of UK manager Phillips & Drew who was sacked in March 2000 due to his dogged devotion to his value style and insistence that the market was in a bubble, which had led to persistent underperformance. Within weeks that bubble had burst and the returns of the fund he had left behind quickly flipped from bottom to top quartile.

Factor crowding: too much of a good thing

In our view, such behaviour significantly increases the risk of bad outcomes, even if it boosts short-term performance. This goes beyond the fact that the fund managers are suddenly investing in companies and sectors with which they have little experience. More importantly, they interfere with the work of the asset allocators, who then run the risk of becoming overexposed to a certain sector or theme. This is known as factor crowding or thematic convergence.

If, for example, a growth manager in 2006 began investing in cyclical mining stocks, short-term returns may well have improved. But those returns would have been driven by the same forces benefiting a value manager, leaving the overall portfolio less diversified than it appeared. When the cycle turned, both the value and growth portions would have fallen together.

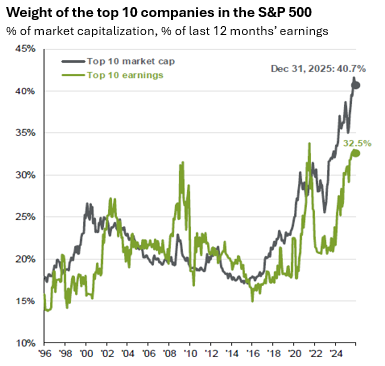

This is particularly dangerous because factor crowding often remains hidden in benign markets, only revealing itself when conditions change and correlations rise. The level of concentration in equity markets today suggests similar dynamics are again at play.1 With a small number of companies driving index returns, and with intense pressure to keep pace with benchmarks and peers, it is understandable that managers may be tempted to loosen their parameters.

The more important question for asset allocators is what this means when the macro regime eventually changes. Apparent diversification may prove illusory if multiple managers have drifted, knowingly or otherwise, towards the same dominant factors.

Figure 1: Concentration of the top 10 companies in S&P 500 at record levels

Know thyself

When considering how to resist the temptation to chase performance, the answer came to me via an Oracle. No, not the company nor Mr. Buffett, but the one in Ancient Greece. Or rather the inscription above the temple at Delphi where the Oracle offered out her prophecies: “Know Thyself”. By understanding clearly what we are, and just as importantly, what we are not, it becomes far easier to remain disciplined. It has never been our intention to try to perform in all market environments, we know this is unrealistic and therefore do not try to do it. In creating the Ten Golden Rules we have distilled this knowledge of what Quality Growth is into a set of guardrails that further protect us from that temptation to drift. Instead, our goal is to offer the purest representation of Quality Growth, irrespective of the market environment.

For asset allocators, the value of manager discipline lies not in avoiding underperformance, but in providing clarity: knowing how each component of a portfolio is expected to behave when regimes shift and correlations rise. As we head into 2026, we don’t know whether the market environment is set to change any time soon. However, thanks to our clearly defined philosophy and our cautious long-term planning, we do know that our Quality Growth style will not change, and that means you know exactly what to expect from us.

1It’s worth adding here, that factor convergence today may be even stronger since you not only have different styles of funds investing in the same names which are generating returns, but you also have the same theme, notably the AI infrastructure build-out, driving different sectors like Utilities and early stage Tech, which intensifies the factor crowding further.

This is a marketing communication / financial promotion that is intended for information purposes only. Any forecasts, opinions, goals, strategies, outlooks and or estimates and expectations or other non-historical commentary contained herein or expressed in this document are based on current forecasts, opinions and or estimates and expectations only, and are considered “forward looking statements”. Forward-looking statements are subject to risks and uncertainties that may cause actual future results to be different from expectations.

Nothing contained herein is a recommendation or an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. The material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment advice. The content and any data services and information available from public sources used in the creation of this communication are believed to be reliable but no assurances or warranties are given. No responsibility or liability shall be accepted for amending, correcting, or updating any information contained herein.

Please be aware that past performance should not be seen as an indication of future performance. The value of any investments and or financial instruments included in this website and the income derived from them may fluctuate and investors may not receive back the amount originally invested. In addition, currency movements may also cause the value of investments to rise or fall.

This content is not intended for use by U.S. Persons. It may be used by branches or agencies of banks or insurance companies organised and/or regulated under U.S. federal or state law, acting on behalf of or distributing to non-U.S. Persons. This material must not be further distributed to clients of such branches or agencies or to the general public.

Get the latest insights & events direct to your inbox

"*" indicates required fields