Google has established itself as the dominant search engine over the past two decades. Today it accounts for more than 90 per cent of the global market and remains by far the most important part of Google’s business, accounting for 57 per cent of revenues. Over the past few months, a lot of media attention has been devoted to the potential threat to this dominance posed by competitor products powered by Large Language Models (LLMs) or “AI”. We note that it is still far too early to tell how these models will evolve or to come to a clear view on how they will affect a multitude of different industries and indeed society as a whole. What we do know is that so far it has had minimal effect on market share.1 There are many factors behind Google’s enduring success as the search engine of choice. This newsletter focuses on one factor that may often be underappreciated — its tight control on the distribution channel.

Distribution channels bring goods and services from producers to end consumers. Despite such a simple concept, distribution is a critical step between value creation and value realisation. It can create or restrain demand for products and services and can exert a strong influence on consumers’ purchasing decisions. As we witnessed in the 20th century, the success of many consumer goods companies was underpinned by their superior distribution clout.

The most well-known case might be Coca-Cola. The company and its network of bottlers comprise one of the most sophisticated and extensive distribution systems in the world and that is one of the key factors contributing to Coca-Cola’s worldwide, long-standing success. If we turn to the Seilern Universe, dominance of the distribution channel is perhaps the most substantial competitive advantage of the global eyewear giant EssilorLuxottica. EssilorLuxottica designs, manufactures, distributes and retails their product portfolio which includes prescription lenses, frames and sunglasses. The company began as a manufacturer of eyewear and gradually came to control the entire downstream distribution from wholesale to retailer. For example, in the US, EssilorLuxottica owns the largest lab network, accounting for more than half of the market. Through both direct ownership and exclusive supply agreements, it further controls the majority of optical chains and independent eye care professionals. And as if this wasn’t enough, the Group also owns the second largest vision care insurance company in the US, adding another layer of protection to its channel dominance.

Yet, these companies are typically viewed as epitomes of 20th century businesses. They produce physical products, for which significant economies of scale can be derived from vast physical distribution infrastructure. But the 21st century has seen rather different, “new” enterprises emerge and prosper. They produce digital products, the distribution cost of which seems substantially reduced by the Internet. In this new digital economy, one may question, can the control of distribution still be a source of a company’s competitive advantage? In our observation, it holds as true as ever.

Returning to Google, the majority of consumers access the Internet via either their mobile or their desktop or laptop computer. Consumer-facing digital products, such as a general search engine, are distributed on mobiles by three specific access points: a browser, a static search bar on the device’s home screen (quick search bar, QSB) and via a search app. For desktops and laptops, the main access point is simply the browser. In all of these access points, Google has managed to become the pre-set default search engine.

The default effect on decision-making has been widely studied and documented. Broadly it states that humans have a strong tendency to generally accept the default option, rather than deliberately change it. Therefore, it provides a non-intrusive way for businesses to influence, or manipulate as some would say, consumer choices. To take advantage of this phenomenon, Google developed a strong product ecosystem. The strength of this product portfolio, combined with contractual arrangements with distribution partners, enabled Google to secure exclusive pre-set default status for its search engine.

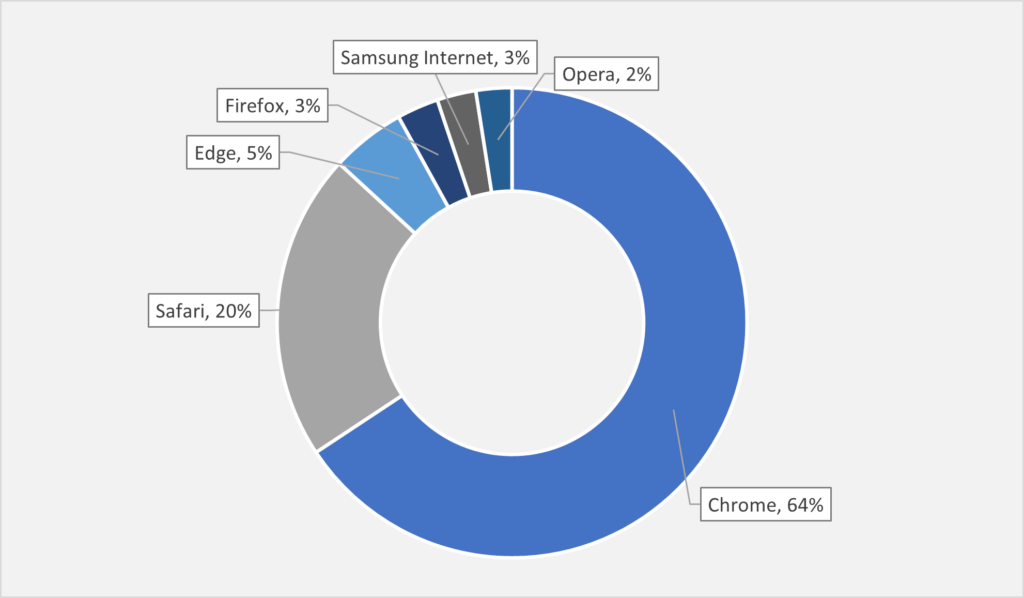

Figure 1: Global Web Browser Market Share

Source: Statcounter, January 2023

As most laptop and desktop users access a general search engine through a browser, Google developed its own browser, first launching Google Chrome in 2008. By 2014, Chrome had become the dominant browser, and today holds 65 per cent of market share worldwide. In order to be the default search engine in the remaining browsers, Google simply pays them. The one exception is Microsoft’s Edge, which leaves Google in control of about 95 per cent of all browser distribution.

There are effectively only two mobile operating systems (OS) in the world. One is Android, technically owned by Google, with about 72 per cent market share globally, and the other is iOS, owned by Apple with about 28 per cent market share. In order to gain default status on all of Apple’s devices, Google pays Apple handsomely. The payment was estimated to be about $10bn in 2020, $15bn in 2021, and as much as $20bn in 2022. Contrasted to this purely financial transaction, it is a little more interesting to look at how Google implemented their control on Android devices.

Although mostly developed by Google, Android is an open-sourced project. That means it is free for anyone to use and install. Yet only a few phone manufacturers use the truly “free” version of Android, and even those few are often forced to do so.[1] One may rightly wonder why this is the case. The primary reason comes down to where the value of a mobile OS is generated. A large portion of this value lies not in the OS itself but in the ecosystem around it. The open source or the “bare” Android system doesn’t have access to the strong ecosystem that Google created around Android. This includes key products such as Google Play (App Store), Gmail, YouTube and some core functionalities such as security updates. These products and services are proprietary to Google and are seen as very important to consumers. Without them, a mobile can be much less attractive to consumers and is less likely to be bought. In order to use the “full” version of Android, manufacturers must work with Google.

For example, manufacturers need to sign several agreements, such as Mobile Application Distribution Agreements (MADAs). This requires phone manufacturers to set Google Search as the default search engine and pre-install a bundle of Google’s products and display them in a prominent position on the home screen, with some apps undeletable. After a 2018 EU antitrust case, EU manufacturers have the choice not to install two apps: the Google Search app and Chrome. But if they do not, they must pay a license fee to be able to install the rest. On the other hand, Google offered incentives – Revenue Share Agreements (RSAs) to major distribution partners, such as original equipment manufacturers (e.g. LG and Samsung), mobile phone carriers (e.g. AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon) and other browsers (e.g. Opera and Mozilla) in exchange for exclusivity. RSAs prevent them from pre-installing any other search engine. Therefore, using both carrots and sticks, Google effectively controls 80-90 per cent of the mobile distribution channel.

Channel dominance was a key source of competitive advantage in the traditional economy for physical goods and services. The example of Google shows that the power of distribution is just as important in the digital economy. What also has not changed in the new economy is the relationship between a product and its distribution. In all examples discussed in this newsletter, each and every one of them – Coca-Cola, EssilorLuxottica and Google Search – made market leading products first and then achieved powerful distribution after. As such, building a strong product, obtaining privileged access to distribution and gaining control over it can effectively raise the barriers to entry and serve as a sustainable competitive advantage.

N. Yu

28th April 2023

1Analysis by Statcounter showed that Google’s share slightly increased from 92.6 per cent to 93.2 per cent between December 2022 and March 2023.

2For example, Huawei and other Chinese phone manufacturers are banned from working with any US organisations as a result of the US-China trade war.

Any forecasts, opinions, goals, strategies, outlooks and or estimates and expectations or other non-historical commentary contained herein or expressed in this document are based on current forecasts, opinions and or estimates and expectations only, and are considered “forward looking statements”. Forward-looking statements are subject to risks and uncertainties that may cause actual future results to be different from expectations. Nothing in this newsletter is a recommendation for a particular stock. The views, forecasts, opinions and or estimates and expectations expressed in this document are a reflection of Seilern Investment Management Ltd’s best judgment as of the date of this communication’s publication, and are subject to change. No responsibility or liability shall be accepted for amending, correcting, or updating any information or forecasts, opinions and or estimates and expectations contained herein.

Please be aware that past performance should not be seen as an indication of future performance. Any financial instrument included in this website could be considered high risk and investors may not get back all of their original investment. The value of any investments and or financial instruments included in this website and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount originally invested. In addition stock market fluctuations and currency movements may also affect the value of investments.

Get the latest insights & events direct to your inbox

"*" indicates required fields